This is an updated version of an essay originally written in 2013.

It was first published by Rockport Publishers.

Richard Linklater’s film “Waking Life” contains a scene where a man (Caveh Zahedi) gives a brief overview of film critic André Bazin’s ideas about God and film. The idea starts with the argument that if photography and film-based cinema are a record of something, be it man, animal or thing, in a space and in a time, then there is a fundamental truth of existence which is captured. And if reality is the work of God, then each frame of a film is the record of a fleeting Holy Moment, or even the face of the divine itself.

It’s a lovely idea. And an ironic one, when you consider that the idea is presented in a film that has been totally digitally manipulated — a subject explored in critic J. Hoberman’s “Film After Film.”

Religious feelings aside, there can be something magical about seeing a person captured on film in a special moment, regardless of how imperfect the image may be. In fact, sometimes the imperfect image has more of a charge than a perfect one. Which leads to the aestheticization of imperfection. For example, the work of photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, whose blurry, shaky, over- and underexposed images had more power than most professional work of his time.

These aestheticized imperfections exist in cinema as well: Jean-Luc Godard’s shaky hand-held camera, Stan Brakage’s scratched film, Michael Snow’s film grain and light leaks, and my current obsession: the lens flare.

The film which elevated the lens flare to a technique was Richard Lester’s Hard Days Night. The film is an exuberant and slightly arch study of The Beatles at the beginning of their careers. The band, and Paul McCartney’s grandfather (“a clean old man”), take a train to London, run from rabid fans, have a few comic interactions, and then appear on television. The whole production had a relatively low budget and was shot in the cinéma vérité style.

And keeping in the vérité tradition, there are a few moments, as the camera moves around the band, where the lights of the television studio flare into the camera. Now this was something that a typical cinematographer would work to avoid. But The Beatles were something entirely different. They represented a new way of being in a post-war modern world. Mass media was beginning to erode the separation between private life and public persona, and this was another opportunity to follow and learn about the band as “real” people. And any obvious attempt to retouch this reality would spoil the moment. The Holy Moment, as any Beatle fan would argue, where we see into the souls of the lads from Liverpool.

The lens flare was an ideal signifier for this new counterculture. The viewer’s experience was no longer mediated and homogenized by the establishment. We were there. We were alive.

And we were exploring uncharted territory.

This free and easy play of light quickly found its way into other counterculture media. Not always a lens flare in the strictest sense, but definitely a stylized imperfect exposure used to evoke a response.

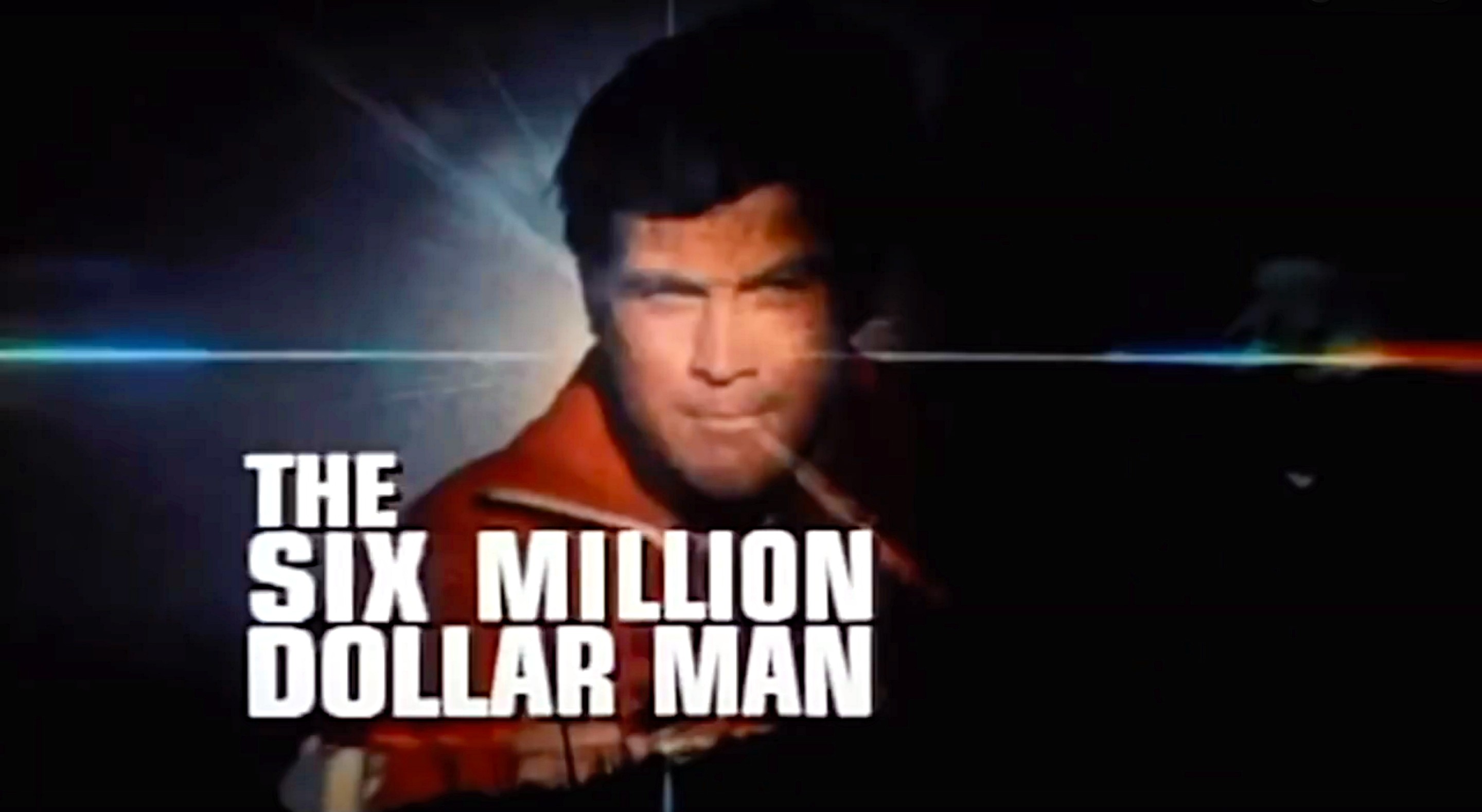

Then in 1973, building on the NASA images, the lens flare took on another meaning: the bright future. Steve Austin, played by Lee Majors, was an astronaut in need of bionic limb and eye replacements after a catastrophic crash. He was the future of mankind. He was The Six Million Dollar Man.

Cinematographically, the series was your basic one-camera, well-lit, episodic hack job. But its opening sequence was pretty complex and layered for its time. That lens flare, centered under his bionic eye, helped shift the effect from a stand-in for actuality to one of dreams and possibilities.

And few convey this dreamy wonder better than Steven Spielberg.

The light in his Close Encounters of the Third Kind obscures as much as it illuminates. When it pours from the alien craft, the brightness prevents us from seeing detail, thus allowing the mind to imagine something beyond our earthly experience.

This is a different kind of Holy Moment. A transcendent one, in the exaggerated sense of Baroque painting. Where what’s beyond is so awesome, we can’t even imagine it.

And as Reubens had his acolytes, so does Spielberg: most notably JJ Abrams, who once described his storytelling philosophy in terms of a mystery box.

“He recalled getting something called a mystery box. On the outside it had a big question mark, and on the inside it had . . . what? Toys, presumably. Tricks, maybe. If you shook the box, you heard them rattling around. But their precise nature wasn’t known. That was the thrilling part, the part that held your imagination captive.”

Frank Bruni, “Filmmaker J. J. Abrams Is a Crowd Teaser,” The New York Times, May 26, 2011

That quote was from an article which was part of the PR push for his film Super 8, in which his love of Spielberg and the lens flare were on full display.

“Well, say that there’s a…there’s no question that I overuse lens flares on occasion. I know that there’s a sort of… The kneejerk reaction from the director of photography is usually…it’s usually, ‘OK, we’ve got to flatten that light because it’s going to flare.’ I think it’s one of those things that you want to make sure that, obviously, it’s…To me it’s such a cool beautiful image, the light through the glass. There are times that I feel like it sort of adds another kind of smart element, and it’s hard to define. But it is a visual taste that I do like. I think there are a couple shots in ‘Super 8’ where I just think I should definitely pull back here or there, but I can’t help myself sometimes.” Interview with J. J. Abrams

The flares in the lower image of the young men, above, really stand out because they obscure without overtly advancing the narrative. That is, beyond a vague sense that something extraordinary is happening.

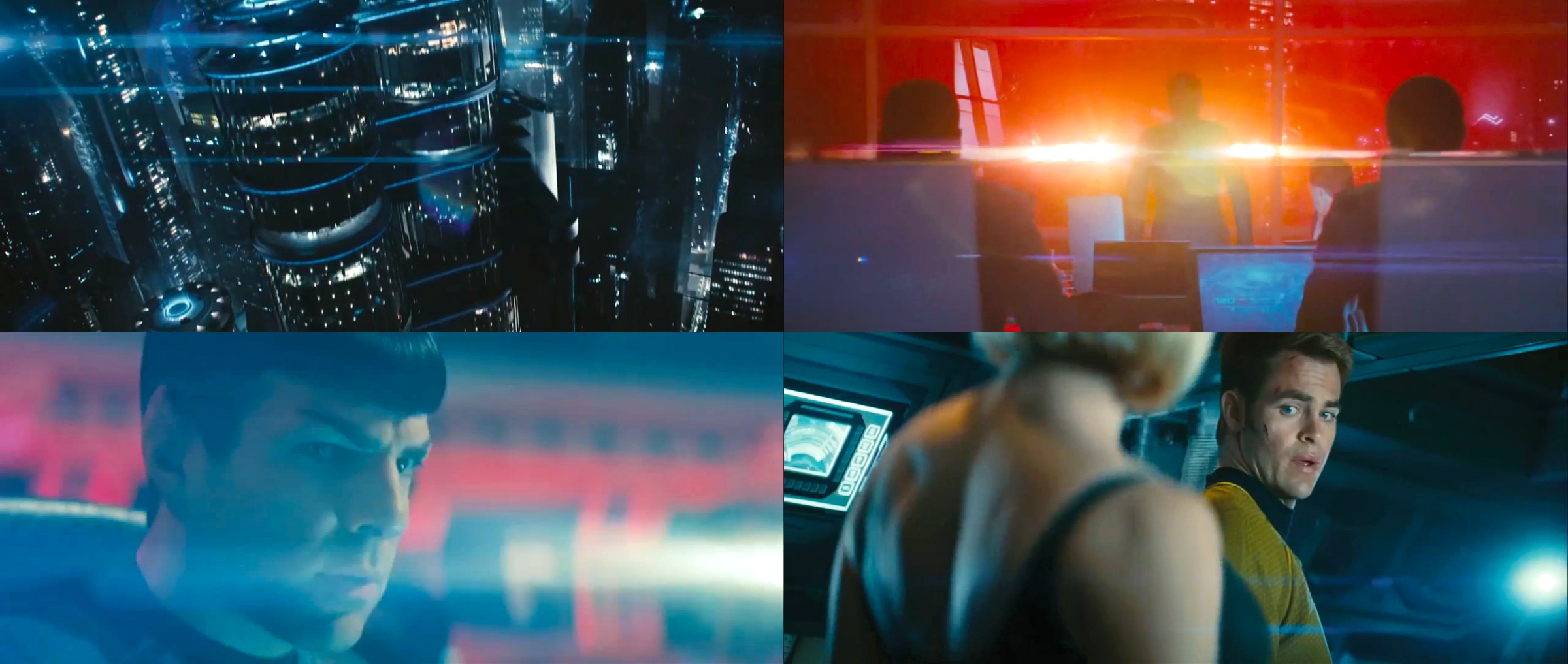

So let’s consider the flares in his version of Star Trek. Lots of dark murky spaces punctuated with blinding flares, and a starship bridge with the worst human factors seen in quite a while. A place so bright, I would worry about finding the photon torpedo button in an emergency.

A place so bright, that the title of the sequel, Into Darkness, looses its full meaning.

Given the general lack of creativity in Hollywood corner offices, the success of J. J. Abrams’ films means the easily-copied aspects of his work will be imitated for years to come. If he’s the current king of science fiction, then Hollywood’s superstitious laws of transitive property dictate that you need lens flares to make a proper sci fi film.

In all fairness, I can’t blame Abrams for compulsively including lens flares in so much of his work. I adore how Jean-Luc Godard designs film titles, and how his edits are so disruptive. And I get a chuckle when Clint Eastwood’s camera boards a helicopter in order to close a film with yet another God’s-eye-perspective zoom out. Every creative person has their tricks and go-to techniques.

I don’t get the sense that Abrams thinks on the critical level that Spielberg does. He admits to overusing lens flare, and it can be hard to define what the flares are trying to do other than create a “techy” atmosphere. Right now, in 2013, I can apply a matte screen protector so my iPhone doesn’t reflect sunlight. So why can’t engineers in Abrams’ future create a starship bridge that doesn’t throw off so much indiscriminate light?

The flaring has reached such a level of absurdity and thoughtlessness, that it appears in role-playing games like Battlefield 3.

The incongruity is that lens flare is a product of a moment captured with a camera. In theory, the Battlefield player is using their eyes, which perceive a greater range of shadow and highlight — without lens flare.

But it looks cool.

In contrast, here’s one frame from Saving Private Ryan which recreates the D-Day invasion.

Speilberg described his process: “Early on, we [Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski] both knew that we did not want this to look like a technicolor extravaganza about World War II, but more like color newsreel footage from the 1940s, which is very desaturated and low-tech.” Kaminski stripped the camera lenses’ protective coating to bring them closer to period technology. “Without the protective coating, the light goes in and starts bouncing around, which makes it slightly more diffused and a bit softer without being out of focus.”

In this case, Spielberg and Kaminski’s flare effects have a critical and aesthetic foundation which gives the film an authentic look and feel. Something which may not contain holy moments as described in Waking Life, but certainly more emotional impact than the unholy moments of excessive lens flares.

This is an updated version of an essay originally written in 2013.

It was first published by Rockport Publishers.